After three years of hosting almost all our 150+ interviews for The History Author Show, I maintain my love for the magic of books and admiration of the people at all levels who bring them to us. But like Mr. Henry Bemis in the iconic Twilight Zone episode “Time Enough at Last,” there are always more books than hours to read. So I’m hoping that the occasional written Q&A will allow me to touch base with and promote authors who catch my eye but who we can’t join for a conversation.

We kick off this feature for 2019 with an author whose book I’ve been dying to cover. His name is Travis Smith and he brings us Superhero Ethics: 10 Comic Book Heroes; 10 Ways to Save the World. Which One Do We Need Most Now? Mr. Smith is associate professor at Concordia University where he teaches political philosophy. He earned his doctorate at Harvard University. He now resides in Montreal, where he “teaches Hobbes, Tocqueville, Plato and Aristotle by day, and fights crime by night.”

So let’s get started, true believers…

The History Author Show: I felt we had an immediate connection when I read about your “pull list” at the local comic book store. In my interview with Bob Batchelor about his book Stan Lee: The Man Behind Marvel, we touched on the bias against this art form that persists, to the point “comic book character” is a pejorative. How did you go about overcoming that negativism to distill the wisdom of millions of stories across several decades of history into Superhero Ethics

?

Travis Smith: From within their burgeoning interdisciplinary field, comics scholars sometimes lament that they get no respect. But I don’t know if the negativism you refer to is as bad as it was when I was younger. Comic conventions are held now over several days in massive venues. Cosplay has gone mainstream. Digital platforms reach readers who’ve never stepped foot in a local comic shop. Thanks to the popularity of superhero movies, even the cool kids know who Ant-Man and Deadpool are. Some negativism persists, however, as we saw when Bill Maher offered some deliberately ignorant provocations upon Stan Lee’s passing.

Popular stories about heroes tell us a lot about a people’s values and ideals, what a society regards as admirable and worthy of imitation. Some cultures regard self-sacrificing saints as most praiseworthy; some prefer idealistic revolutionaries and other holy warriors. We can better appreciate or criticize a society, including our own, by looking at its models of heroism. As a product of modern society, superheroes reveal a lot about what’s commendable about liberal, democratic, technological, secular, commercial society—or what’s exaggerated within it, or missing from it. Their worldwide appeal furthermore suggests that they speak to concerns and aspirations that exceed the preoccupations of late modern Western society. Anyone who wants to engage in serious cultural criticism but chooses to dismiss superhero stories seems willfully prejudicial. Stories that deal with themes like justice and responsibility, particularly when they are consumed by young people, should not be treated with indifference.

But if your question was aimed at me personally, I don’t worry if other people share my tastes. Everybody’s entitled to their own likes and dislikes and their own standards of better and worse. I’m no subjectivist, mind you; I’m convinced that there are objectively better musicians, for instance, and superior works of literature, too. Comic book readers shouldn’t limit themselves to reading only comic books. As a liberal with admittedly democratic sensibilities, however, I don’t think we should be too judgmental regarding people’s hobbies and other sources of satisfaction.

It’s easy to mock anything you’re not into. Grown-ups who follow hockey on television like watching dudes in goofy shirts glide on ice slapping rubber disks with bent sticks—and I say that as a sports fan myself. What’s worse than taking pride in putting down other people’s pastimes is when people are so desperate for validation that they demand everybody else’s respect for their preferences. Worse still is when people accuse others of being deficient or blameworthy for not liking what they want them to like. We could all stand to care a little less, not only about other people’s preferences, but about what other people think of our own—especially when it comes to our leisurely activities.

HAS: Batman is one morally complex character you deal with in Superhero Ethics. Over the decades he’s evolved from a masked detective to a hero fighting cartoonish (even for comic books) villains and back again into a more realistic vigilante. Which incarnation of Bruce Wayne’s alter ego interested you the most for the purposes of your book?

TS: Since the mid-1980s, the Dark Knight Returns and Year One have cast long shadows on everything Bat-related. I remember encountering the Denny O’Neil version in 1988’s reprint series The Saga of Ra’s Al Ghul and preferring that. Recently, I (re-)watched the entirety of The Animated Series with my son and can’t help thinking it might be the best depiction of Batman because it incorporates all of the essential elements while eschewing all excesses.

In Superhero Ethics I try to identify the common core within each character that makes it possible to identify any variation on them as version of them. My book also emphasizes takes on characters from feature films for the sake of remaining accessible to a general audience. I didn’t want having read ten thousand comic books to be a prerequisite for following along.

The aspect of Batman I focus on in Superhero Ethics is his quest for justice through rational control. Batman operates as if reason, discipline, and unlimited equipment will conquer the tragic conditions of the world. The scene in the Christopher Nolan trilogy that best captures this trait is found in The Dark Knight when we learn that Batman has turned every cell phone in Gotham City into a surveillance device to spy on everyone. In the comics, Batman’s “Brother Eye” satellite system is a similar manifestation of this temptation. Of course, there is no way that such an invasion of people’s privacy could turn out well, however well-intentioned. Social credit systems are implemented by despotic governments, after all. Lucius Fox tells Batman it’s unethical, as if Batman didn’t already know that. At least Batman knows that it is good he doesn’t have Superman’s powers because then it would be too difficult for him, on his own terms, to stop himself from taking over the world for everybody’s own good. If you’re interested in exploring Batman’s moral complexities and psychological complexes, I cannot recommend Tom King’s current run on the ongoing Batman series enough.

HAS: You discuss the impact Superman: The Movie made on you at age 5. Many adult comic book readers outgrow the last son of Krypton because we just can’t relate to his perfect morality, but like Captain America he served as inspiration to Allied soldiers fighting World War 2. People today long for the moral clarity of that fight against fascism. Do you hope Superhero Ethics

HAS: You discuss the impact Superman: The Movie made on you at age 5. Many adult comic book readers outgrow the last son of Krypton because we just can’t relate to his perfect morality, but like Captain America he served as inspiration to Allied soldiers fighting World War 2. People today long for the moral clarity of that fight against fascism. Do you hope Superhero Ethics helps them find it?

TS: In the book I do discuss how the qualities that make Superman seem divine may make him too extraordinary for us to imitate. I argue, however, that he better represents the modern romantic or idealistic secularization of biblical ethics than biblical ethics properly so-called. There’s a lot of Kant in Clark Kent.

I conduct my analyses in Superhero Ethics in a way that downplays not only the “super” part of superheroes but also the “hero” part, asking what these characters have to say about how we non-super, not-that-heroic individuals should handle our less fantastical, more mundane lives. Is giving people more clarity in the fight against fascism what we really need right now? I’m wary of inflaming the impulse to be a hero or seek a champion. In the age of social media, we are already tempted to vilify those with whom we disagree in order to present our opposition to them in the most heroic light.

The problem with taking Captain America as a role model is that, as a super-soldier, he reminds us that unity is something we are most likely to find and sustain under conditions of war, where the enemy is known and punching them is hailed. I’d rather people were less eager to call each other fascists.

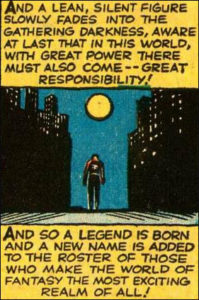

HAS: Throughout human history, the Old and New Testaments have remained an inspiration and ethical guide. One character you look at through that lens is Spider-Man. How do the ethics of Spider-Man’s credo, “With great power, comes great responsibility,” evolved (or perhaps devolved) as Western Culture has moved farther away from the Judeo-Christian traditions?

HAS: Throughout human history, the Old and New Testaments have remained an inspiration and ethical guide. One character you look at through that lens is Spider-Man. How do the ethics of Spider-Man’s credo, “With great power, comes great responsibility,” evolved (or perhaps devolved) as Western Culture has moved farther away from the Judeo-Christian traditions?

TS: I make an effort to persuade my students that if they really want to understand the society in which they’re immersed, its heritage as well as its movements for change, they would benefit from reading the Jewish and Christian scriptures. When I finally read them for myself, I remember regularly thinking, “So there’s where that comes from!” Similarly, I wish that preachers in these traditions today would read more in the history of philosophy so that they could better witness how their religious teachings have been altered or co-opted by hostile sources. Taking a philosophical perspective, I try to explain to my students that religious traditions can relate many truths independent of whether or not they are, on the whole, ultimately and absolutely true. Spider-Man’s motivations are rooted in the biblical tradition and his behavior reflects the experience of persecuted religious communities, but his moral message is not dependent the verity of any branch of the Judeo-Christian tree of knowledge.

The lesson that Uncle Ben taught Peter Parker is important as a corrective to the narrative today that categorizes people into either the privileged, empowered elite who are responsible for dominating, exploiting, and oppressing everybody else, and the disempowered, disenfranchised, helpless, blameless victims who couldn’t possibly be expected to take responsibility for themselves. Spider-Man’s motto reminds us that we all have power—indeed, great power—simply as human beings. That power allows us to do tremendous harm to each other or to be of real benefit to each other. The newly released Into the Spider-Verse draws attention to this lesson explicitly. It is so easy for any of us to decide that we aren’t responsible, whether for ourselves or for what good we could do for each other, on account of the misfortunes and mistreatments we’ve endured. At least, that way forward seems easy—until we see what trouble we’ve gotten ourselves into by giving into it.

The biblical God could force everyone to behave like a good person should, but he doesn’t. He could impose systemic justice on the world, but he does not. He doesn’t even tell his followers to seize political power in this world on his behalf. The proper responsibility that anyone can take for other people has limits. No one should presume to take full responsibility for anyone else, let alone everyone else. But as Spider-Man illustrates, there is still a lot that even a beleaguered individual can do to exercise their native powers to come to the assistance of others, even if only to be a good neighbor.

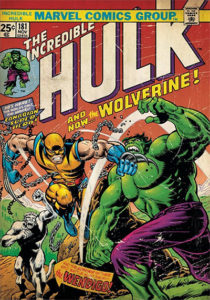

HAS: One of comic fandom’s favorite matchups are between The Hulk and Wolverine, both half-man, half-beast characters who struggle to maintain their humanity. That’s a pretty fair assessment of the role ethics plays in the advancement of civilization. What new insights did you gain from your analysis of those characters in Superhero Ethics

that maybe you missed as a young person caught up in their adventures?

TS: Ha! What aren’t we oblivious to as young people? As a youth, I loved The Incredible Hulk on TV. “The Lonely Man Theme” still makes me feel maudlin. But I sheepishly confess that as a preteen and early adolescent, Wolverine was my favorite. To be fair, no character was cooler in 1980s. I was unaware at the age of thirteen what all the adamantium injections and mental violations were metaphors for. Nor did I perceive how disturbing it is that Wolverine replicates his own victimization every time he uses his claws. For stabbing.

TS: Ha! What aren’t we oblivious to as young people? As a youth, I loved The Incredible Hulk on TV. “The Lonely Man Theme” still makes me feel maudlin. But I sheepishly confess that as a preteen and early adolescent, Wolverine was my favorite. To be fair, no character was cooler in 1980s. I was unaware at the age of thirteen what all the adamantium injections and mental violations were metaphors for. Nor did I perceive how disturbing it is that Wolverine replicates his own victimization every time he uses his claws. For stabbing.

HAS: There’s one question above all others that I wanted to ask when I received Superhero Ethics. It involves three characters. They are Superman, Batman and Optimus Prime. When we were growing up, these heroes all shared a single defining characteristic: They would not take a life. Yet in the recent films, we’ve seen all three execute foes. What do you think that evolution — or devolution — says about the ethics of society reflected in these pages?

TS: When I was a kid even the villains in children’s entertainment didn’t kill. It was shocking when Megatron killed Brawn, Prowl, Ratchet, and Ironhide. (I was glad about Ironhide.) After watching everybody parachute away to safety or otherwise decant themselves from demolished vehicles over the years on G.I. Joe, I remember how striking it was when the same did not always happen on the X-Men cartoon.

It’s remarkable that we ever found ourselves in a society in which we could imagine heroes who refused to take a life. It says something about the kind of society we imagine ourselves to be, the standards we believe we should live up to, that we get disappointed whenever our heroes fall short of that noble ideal. This is the kind of thing I keep in mind whenever I hear critics of our society tell us how bad we are. We actually demand a government that is efficient, competent, and serves the public good. Amazing! We even expect our police to be non-corrupt and our armed forces to be nonpredatory. Extraordinary!

HAS: One way people deal with the bias against comic book heroes is to say, “No, no. They’re just playing the same role as Greek mythology in our culture.” Do you find that a useful comparison?

TS: My friend Adam Barkman teaches a course on “Philosophy and Superhero Mythology” at Redeemer University and has written books like Imitating the Saints on the subject. There’s validity in approaching the subject in that fashion, although it is not my approach in Superhero Ethics

. Against those who think that superhero stories are too juvenile or frivolous for philosophy professors to consider, however, I do point out that Plato had no compunction about discussing the Homeric legends in his dialogues.

Do superheroes stories play the same role for us as the myths did for the ancient Greeks? Let’s set aside the fact that we all know superheroes are make believe, yet we can wonder how much the ancient Greeks truly believed in the stories about their gods. Superheroes are product of a liberal and democratic culture. They are intended to represent us ordinary, free and equal people, metaphorically—or so I argue. At least, I think the best stories about them present them in such a manner rather than as demigods or messiahs.

HAS: You write in your introduction that some readers may complain that you’re inferring things that the author didn’t intend, but that, quote, “works of art often exhibit different meanings and significance beyond the intention of the artist.” Nobody argues with a person who finds meaning in Shakespeare or a Rembrandt, but not so comics. What tools will readers of Superhero Ethics develop to deal with those who mock the idea that people could get meaning from, say, Captain America’s example?

TS: Imagine if Shakespeare really did intend everything anyone has ever attributed to him! But he’s brilliant enough without granting that supposition; that he’s so evocative proves his genius. There a regrettable tendency today to try to deflate and deprecate the great literature of the past instead of appreciating and learning from it. In Superhero Ethics I take literature that is commonly regarded as not that great and endeavor to show that we can nevertheless extract much from it if we read it generously, remaining open to the possibility that its success implies that we can learn something worthwhile about ourselves by reflecting on it. Think of how Socrates supposed he could begin an ascent to philosophy from ordinary conversations on everyday subjects with anyone he encountered.

Even if the comic book creators of decades past thought of themselves as only producing disposable amusements for kids, it is plain that they were drawing on their own learning in history, literature, and religion in their storytelling. There has always been a tendency in good children’s literature to include content that only a more mature reader will discover. I have recently become convinced that all kinds of entertainment produced in the post-war period, through the 1950s and into the early 1960s, was subtler and smarter than it appears at first glance. It may have presented itself in a deliberately naïve and squeaky-clean manner, but the generation of people who survived the Second World War were not so simple. It is essential to the narrative that has been constructed about the enlightenment of late 1960s that the art of the era that immediately preceded it must be belittled and maligned.

HAS: In Superhero Ethics you offer Thor’s “noble commitment to old-fashioned courtesy and decency” as a possible antidote to “the inflammatory rhetoric and bitter divisiveness of the present.” Was the Asgardian a role model for you as a young person, and if so, how did you follow his example short of wielding an old ball-peen hammer a mini Mjölnir?

TS: Walt Simonson’s run on Thor remains an all-time favorite, but no, I didn’t think of Thor as a role model then. I was partial to Green Lantern—which I now realize was evidence of some deficiency in me. In Superhero Ethics

TS: Walt Simonson’s run on Thor remains an all-time favorite, but no, I didn’t think of Thor as a role model then. I was partial to Green Lantern—which I now realize was evidence of some deficiency in me. In Superhero Ethics I argue that Thor’s hammer can be read metaphorically for all of the abilities that human beings possess that can be used to build or destroy, including our speech. Throughout Superhero Ethics

I strive to read the superpowers that superheroes possess as metaphors for the ordinary—and often extraordinary—abilities that we human beings possess. Yes, I’m aware that Thor’s hammer (notoriously short-handled) is more readily read as a metaphor for something else. So is Green Lantern’s power ring, thrust awkwardly into a power battery. But that sort of analysis already abounds in comics studies, so I made the conscious decision to forego these preoccupations in my book, preferring to leave them to others so infatuated. I wanted to focus on considerations of character, which in old-fashioned terms means prioritizing souls over bodies—something that is definitely out of fashion nowadays.

HAS: I found your pairing of Iron Man and Green Lantern interesting. You note that Iron Man’s film busted the box office but Green Lantern failed. “You will believe a man can fly,” or have other enhanced abilities we share, but there are limits to the suspension of disbelief. And yet the Lanterns aren’t meta-humans. They’re just noble guys who the ring choses for their character, similar to only the worthy wielding Thor’s hammer. They should be relatable. Why do you think this ethical hero fighting evil has lost his appeal in the past several decades while others prosper?

TS: I don’t think you can make a generalizable claim that Green Lantern has lost his appeal, even if handing creative control over his stories to Grant Morrison in late 2018 seems like something of a Hail Mary. The Green Lantern movie was released at a time when the “Sinestro Corps War” and “Blackest Night” storylines had reinvigorated the GL corner of the DC Universe with bursts of compelling and imaginative storytelling. It is unfortunate that the Green Lantern film flopped. The grim and gritty quality of the DC Extended Universe kicked off by Man of Steel is something of an overreaction to the poor reception of Ryan Reynolds’s lighthearted Hal Jordan. Plus, GL made the mistake that too many sci-fi movies make: being too enamored with awesome special effects and less concerned with character and story.

The Green Lantern Corps is so diverse that there should be a ring-bearer among them for anyone to identify with. Guy Gardner was always my guy. That said, in Superhero Ethics I argue that the diversity found within the Green Lantern Corps is somewhat unbelievable given the concept’s basic conceit. A group made up of the most fearless and honest members of any race should probably be extremely similar in character despite their anatomical differences. They should be almost interchangeable, in terms of their personalities, like the auxiliary guardians of Plato’s Republic would be—considerably more uniform than even the U.S. Marine Corps. If Green Lanterns actually were the kinds of creatures their premises specify, they would be totally unrelatable to the average comic book reader.

HAS: It occurred to me while reading your book that “ethics” isn’t something we teach much in public life. In fact, we most often hear the word in the negative, that is to say a quality some high-profile person is lacking. Do you think that as we’ve lost heroes in real life, we’ve been more drawn to fictional ones who won’t let us down?

TS: In a certain sense, “ethics” is always being taught, whether we admit it or put much conscious effort into it. Society is always trying to shape people’s habits, affect their attitudes and outlooks, and steer their efforts. Ethics never goes away.

In Superhero Ethics

In Superhero Ethics I use far-fetched stories about incredible characters with out-of-this-world abilities to reflect on questions of character that pertain to us ordinary mortals. They’re excellent resources with which to work for the purpose of engaging in friendly criticism of what passes for ethical education today. Superhero stories arise out of modern commitments to freedom, equality, and justice, but they also remind us of qualities we tend to suppress or discourage in modern discourse, such as courage, honor, and responsibility. In the book I offer some additional thoughts on the uneasy and complicated relationship that modernity has with the very concept of heroism.

HAS: I like to ask authors to make their pitch when I wrap up live interviews, so let’s do the same here. Why should readers who have never read about these characters — or those like us who had a pull list at our local comic book store — pick up Superhero Ethics to get analysis of their view of the challenges we face in the real world?

TS: Superhero Ethics was not written only for an audience of comic book readers and superhero moviegoers. If you’re interested in ethical questions and wondering what this astonishingly popular genre says about those issues today—about the kinds of lives we should strive to live in an imperfect world in order to be good and happy—then I have strived to render these fanciful stories familiar to satisfy your curiosity.

HAS: Travis Smith, thank you so much for answering these questions in writing. Superhero Ethics drew me in as much as any title that doesn’t come in a plastic comic bag. It gave me a lot of food for thought just as you intended, and I hope readers will check it out to ponder some of these questions as we wrestle with creating a better world.

TS: Thank you, Dean, for the opportunity to be a part of The History Author Show. Ever upward!

HAS: I appreciate you making the time. “Excelsior!”