We welcome co-authors David Wolman and Julian Smith to chat about ranchmen unlike any you’ve read about before. This may not be our first rodeo, as people say, but it’s certainly a rodeo like no other. Their very special book is Aloha Rodeo: Three Hawaiian Cowboys, the World’s Greatest Rodeo, and a Hidden History of the American West.

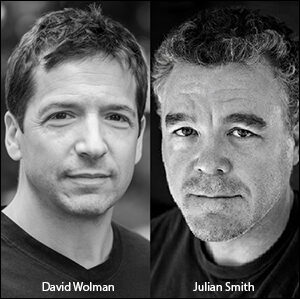

David Wolman is a Contributing Editor at Outside. He has written for the Wired, the New York Times, New Yorker, Nature, and many other publications, as well as having his work anthologized in the Best American Science and Nature Writing series. He’s author of The End of Money

David Wolman is a Contributing Editor at Outside. He has written for the Wired, the New York Times, New Yorker, Nature, and many other publications, as well as having his work anthologized in the Best American Science and Nature Writing series. He’s author of The End of Money, Righting the Mother Tongue

, and A Left-Hand Turn Around the World

.

Julian Smith received a Banff Mountain Book Award and a Lowell Thomas Travel Journalism Award for Crossing the Heart of Africa: An Odyssey of Love and Adventure. The coauthor with Jason A. Ramos of Smokejumper: A Memoir by One of America’s Most Select Airborne Firefighters

, you’ve enjoyed his work in Smithsonian, National Geographic Traveler, Wired, Outside, and the Washington Post, among other publications.

For more, visit JulianSmith.com and David-Wolman.com. You can also follow them on Twitter @JulianWrites and @DavidWolman or Instagram @JulianSmith and @DavidWolman.

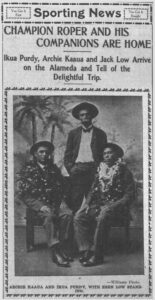

THE HISTORY AUTHOR SHOW: I love browsing through old newspaper archives (see below) or finding that single anecdote in history that sparks hours spent searching for whatever happened to the people who’ve caught my interest. So take us back to that origin moment for Aloha Rodeo. Which of you first discovered the story of Ikua Purdy, Jack Low, and Archie Kaaua and hooked the other on this fascinating tale?

David Wolman: Many people in Hawaii are aware of the quick-summary version of this story. When I first learned about it, after seeing a statue of Ikua Purdy, I had this rush of questions. I wanted to know Purdy’s background, the broader history of ranching in the islands, the adventure in Wyoming, and what it all meant to people back then. Little had every been written on this subject, especially for a mainstream audience, and so I decided to take a crack at it.

THAS: Horses are key to a rider’s performance, something so obvious that we may overlook it. But having worked with horses during my veterinary studies, I know this is not as simple as a stock car driver purchasing a new ride and tweaking it. Just how did these cowboys go about securing the right mounts for the competition thousands of miles and an ocean away from their stalls?

Julian Smith: The paniolo were loaned horses by their hosts in Cheyenne, which proved to be a sensitive issue when it came to the roping competition. A cowboy and his horse have to be in sync when to chase and bring down a sprinting, 400-pound steer. And that teamwork doesn’t stop with getting a lasso on the animal; a horse has to know to stop on a dime, letting the rider leap off to make the tie, while keeping the rope tight enough so the steer stays down but doesn’t get dragged. Unfamiliar mounts means a disadvantage—no question. On top of that, the paniolo weren’t given horses to train with until shortly before the competition. (Stories vary from a few days to a few hours.) In any case, they were competing on horses they had just met, relatively speaking, in an event where the connection between rider and mount is crucial.

THAS: Readers will come across the term paniolo in Aloha Rodeo. How does the origin of the word set the scene for the introduction and development of Hawaiian cowboy culture?

Julian Smith: When British Captain George Vancouver brought the first longhorn cattle in Hawaii in 1897, the king issued a royal edict that made harming them a crime punishable by death. In no time, the “king’s cattle” were reproducing in huge numbers, and then running rampant over every island where they were introduced, digging up garden plots and goring people with their deadly horns. The Hawaiians clearly needed help, so the king sent for a handful of Spanish vaqueros from New Spain (now Mexico and California) to teach them how to wrangle cattle. That was the birth of the paniolo tradition, as well as the word itself—a Hawaiianized version of Spanish.

THAS: Author Tom Clavin writes, “Aloha Rodeo accomplishes the bronco-busting trick of combining thorough research with a fast-paced narrative. Who knew that three young men from Hawaii would transform the sport of rodeo, bring pride to their homeland, and be at the center of such a riveting story.” Since I interviewed Tom for his books Wild Bill and Valley Forge, I asked him what he’d ask about Aloha Rodeo. He said, “One of the aspects of the book that impressed me was the history of rodeo on Hawaii. I’d want to know more about how that research was done.” So have at it. Describe how you handled your division of labor as co-authors, and specifically the task of digging up facts in Hawaii – which, as research locations go, sounds pretty great.

THAS: Author Tom Clavin writes, “Aloha Rodeo accomplishes the bronco-busting trick of combining thorough research with a fast-paced narrative. Who knew that three young men from Hawaii would transform the sport of rodeo, bring pride to their homeland, and be at the center of such a riveting story.” Since I interviewed Tom for his books Wild Bill and Valley Forge, I asked him what he’d ask about Aloha Rodeo. He said, “One of the aspects of the book that impressed me was the history of rodeo on Hawaii. I’d want to know more about how that research was done.” So have at it. Describe how you handled your division of labor as co-authors, and specifically the task of digging up facts in Hawaii – which, as research locations go, sounds pretty great.

David Wolman: We spent some time in the Hawaii State Archives, the Bishop Museum, and the North Hawaii Education and Research Center in Honokaa. We also interviewed local experts and descendants of some of the protagonists. But contemporary newspapers were probably our most valuable resource. And not just newspapers from Honolulu; towns like Hilo and Lahaina had newspapers that covered rodeo as well. There were also Hawaiian language papers. For those we had a translator’s assistance.

THAS: Tom Clavin also made an observation which speaks to the uniqueness of Aloha Rodeo. “It seems to me, most major publishers don’t take notice of stories from Hawaii because it is the most remote state.” How did you have to really hone your pitch to get a publisher consider the topic, or did the story hook them the way it clearly hooked me?

David Wolman: The story hooked them in the initial interest sense of it, but we had to build the case that this more than a flash-in-the-pan sporting victory. That’s where some of the other threads tie in: a protracted sports rivalry, the era of American imperialism, a more inclusive (and accurate) view of cowboy history, Cheyenne’s ups and downs, and the idea of upsetting conventional and often simplistic thinking about the American West.

THAS: Driving cattle is dangerous enough on the wide-open plains, and then the paniolo have to face things like underwater obstacles and even sharks. (Yes, sharks.) How did their day-to-day environment on a Pacific island translate to competing smack in the middle of a continent?

Julian Smith: The paniolo worked under incredibly difficult conditions, starting with roping wild cattle in the dense forests at elevations of 6,000 feet or higher. Then they had to guide the animals down out of the forests, across barren lava fields, and onto the beach at places like Kawaihae. The final step was driving steers straight into the breakers and swimming them out to waiting boats, where they were hauled aboard for shipment. (That’s where the sharks came in.)

THAS: A horseman’s equipment is always specific to the task. Riders may know, for example, the difference between an English and Western saddle. How did the gear Ikua Purdy, Jack Low, and Archie Kaaua used differ from those of their mainland counterparts?

Julian Smith: Paniolo equipment was based on that of the Spanish vaqueros but was specially adapted for use in a wet climate and dense jungle. The general setup was the same: hat, lasso, leather chaps. But their hats had particularly wide brims, sometimes woven out of tropical leaves, to provide protection from sun and rain. Paniolo carried ponchos to keep dry during downpours and wore thick leather foot guards called tapaderos for protection from thorny vegetation and lava rocks. The most distinct piece of gear was the kaula ‘ili, or lariat. Instead of the manila-fiber cord used by mainland cowboys, paniolo wove their lariats out of braided rawhide, which lasted longer in the tropical climate.

THAS: You mention Theodore Roosevelt among the founders of the Cheyenne Frontier Days, so we see him play a role in this forum for the Hawaiians to demonstrate their skills. I recalled a moment during TR’s service in Cuba. Some cowboys decide they’ll play a joke on a New York City dude by giving him an unbroken horse, only to learn he’s a champion polo player at Harvard who easily handles the mount. Riding is something where you can’t fake it until you make it, so to speak, and therefore skill is a great equalizer. What were those early moments where these outwardly very different cowboys demonstrate they have the right stuff?

Julian Smith: Jack Low was the first paniolo to compete, on day one of the three-day competition. But his horse let the rope go slack, and his steer got back on its feet three times. To make things worse, Jack’s asthma kicked in amid the struggle and dust. As a result, his time (2 minutes 25 seconds) was anything but impressive. It’s easy to imagine how blasé the locals were feeling about the Hawaiians’ chances at that point. It wasn’t until day two, when Archie Kaaua and Ikua Purdy had their chance, that the Cheyenne crowd witnessed what a paniolo could really do. Archie roped his steer in 1 minute 9 seconds, the fastest time so far. Then Ikua beat Archie by six seconds. That performance secured them both a spot in the finals the next day and shifted the attitudes of local residents and competitors from disdainful curiosity to genuine concern.

THAS: TR wrote in Ranch Life and the Hunting Trail

THAS: TR wrote in Ranch Life and the Hunting Trail that a cowboy possesses “to a very high degree, the stern, manly qualities that are invaluable to a nation.” What do you hope young men in particular will find inspirational about the story of the Aloha Rodeo — although, by all means speak to anyone who’s trying to break into a field from the outside.

Julian Smith & David Wolman: The stereotypical American cowboy is stoic, tough, humble and supremely self-reliant—all great qualities, in moderation. The story of the Hawaiian paniolo in Cheyenne, however, is about young men who ventured far outside their comfort zones to pit themselves against the best of the best in an unfamiliar, almost alien setting. Now you don’t necessarily have to travel 4,000 miles across an ocean and half a continent to put yourself in a similar situation. But regardless, the keystones are confidence and courage, both of which can take you a long way.

THAS: How do you hope readers will view the story of these cowboys taking their skills to the mainland to compete under their own flag, so to speak, against the larger struggle of Hawaiians to maintain their unique culture even as they’re absorbed to the world beyond their shores?

David Wolman: I do like to think about what happened that summer in Cheyenne is that the paniolo, through their actions, said to the United States on behalf of the Hawaiian people: You may think you own us, but you don’t.

THAS: You quote a newspaperman learning from the performance in Cheyenne that “the Hawaiian Islands are something more than a hula platform in the mid-Pacific.” Here over 100 years later, images from tourism ads and TV shows like Magnum P.I. or the Brady Bunch (and, perhaps, the attack on Pearl Harbor or memories of a vacation) round out the mainland’s view of the islands. Say someone’s on a flight to Hawaii as they read our interview and want to download Aloha Rodeo to devour on the flight. When they land, what do you hope they’ll seek out about the enduring culture that spawned Purdy, Low, and Kaaua?

David Wolman: Get up into the high country. On Hawaii especially but on the other major islands as well. Take a moment and consider that in 1900, a third off all the acreage of the archipelago was allocated to rangeland. This history was, and remains, central to understanding and experiencing modern-day Hawaii. As for more specific things to seek out, there is the wonderful Paniolo Heritage Center in Waimea, as well as many horseback riding tours on offer throughout the islands.

THAS: You write in your epilogue of being on a 2018 trip to Mauna Kea where, quote, “Everyone nods in agreement about the lasting impact of the 1908 victory in Cheyenne.” These men are local heroes, legends even. As co-authors who live in Portland and are not native Hawaiian, how did you approach this story to show sensitivity and respect, and cast Aloha Rodeo as an American story without erasing the fact that it was a singularly Hawaiian achievement?

David Wolman: We were sensitive about this question from the very beginning. How do we participate in this conversation about rethinking how we think about the American West, as both idea and place, without commandeering someone else’s story or writing it in a way that suggests we believe our word is the final word? We took a number of steps to try and ensure that the research, writing, and editing were conducting in a respectful manner.

For example, written accounts of the arrival of the first cattle in Hawaii are all by white mariners. How does one read them? How reliable is that information? Setting aside the bigotry and colonialism for a moment, these people were just flat out ignorant of the culture they were interacting with. So all of that needs to be addressed—not just considered, but addressed in the text.

We also talked to as many people as we could, especially during the writing and editing phase, to see how certain ideas, phrases, or even whole passages read to Hawaiian readers and scholars of island history. They helped us understand that, provided we approached the project with a sense of humility, remained aware of our perspective as outsiders, didn’t make broad assumptions or judgments, and took deliberate steps to counterbalance our biases, the value of getting this overlooked slice of history out to a wider audience would outweigh the critique that this wasn’t our story to tell.

We also talked to as many people as we could, especially during the writing and editing phase, to see how certain ideas, phrases, or even whole passages read to Hawaiian readers and scholars of island history. They helped us understand that, provided we approached the project with a sense of humility, remained aware of our perspective as outsiders, didn’t make broad assumptions or judgments, and took deliberate steps to counterbalance our biases, the value of getting this overlooked slice of history out to a wider audience would outweigh the critique that this wasn’t our story to tell.

THAS: I like to ask authors to make their pitch when I wrap up interviews, so have at it. Why should readers who’ve maybe never been to Hawaii or gotten close to a saddle, pick up Aloha Rodeo to meet these three exceptional cowboys?

Julian Smith & David Wolman: We think this is a rollicking yarn, first and foremost, so we want readers to enjoy it. Beyond that, we hope to complicate people’s view of the American West, but in a way that readers savor. We should all delight in these lesser known stories, not just because they’re damn entertaining, but also because they enrich our understanding of our history by revealing how diverse and fascinating it really is.

THAS: Julian Smith and David Wolman, thank you so much for taking the time to answer some questions about Aloha Rodeo: Three Hawaiian Cowboys, the World’s Greatest Rodeo, and a Hidden History of the American West. It’s been a pleasure to meet these three men, witness their triumph, and now to play a small part in spreading the word of their legend.

Julian Smith & David Wolman: Aloha!