We welcome Duncan Ryūken Williams with some enriching insights about his book, American Sutra: A Story of Faith and Freedom in the Second World War

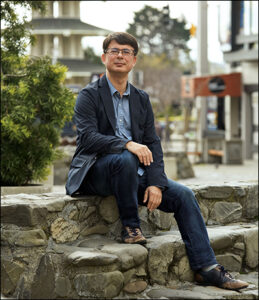

We welcome Duncan Ryūken Williams with some enriching insights about his book, American Sutra: A Story of Faith and Freedom in the Second World War. Our guest was born in Tokyo to a Japanese mother and British father, growing up in both their native countries before moving to the United States to pursue his studies. He earned a Ph.D. in Religion from Harvard and is now Professor of Religion and East Asian Languages & Cultures, and the Director of the USC Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture.

Duncan Ryūken Williams previously held the Shinjo Ito Distinguished Chair of Japanese Buddhism at UC Berkeley and served as the Director of Berkeley’s Center for Japanese Studies. In 1993, he was ordained as a Buddhist priest in the Soto Zen tradition and served as the Buddhist chaplain at Harvard University from 1994-96. He last published The Other Side of Zen: A Social History of Soto Zen Buddhism in Tokugawa Japan, and he’s edited or co-edited seven others.

THE HISTORY AUTHOR SHOW: First, thank you for your time and this read. I love a book that adds to my understanding of the world, especially when I didn’t realize that hole in my knowledge existed. For example, a very basic item: I’ve never had to address a Buddhist priest. What would your title be in that capacity?

Duncan Ryūken Williams: Generally, Buddhist priests tend to have “Ven.” or “Rev.” before their names, so some people call me Rev. Duncan or Rev. Williams. In the Japanese Buddhist tradition, we also use the more informal word for teacher “Sensei”, so some Buddhist community members call me “Duncan Sensei” or “Williams Sensei” as well.

THAS: See, I’m learning already – and unlike some producers in the media used to say when I worked in TV, “learn” is not a dirty word. After all, you didn’t just write American Sutra for readers familiar with Buddhism. I do wonder about that process. How did you go about ensuring that American Sutra would be accessible to as broad an audience as possible?

Duncan Ryūken Williams: It was an interesting challenge to write a book that would be recognized by specialists as making a substantive contribution to the history of American Buddhism as well as to studies on the WWII Japanese American internment, but also be accessible to a broader reading public. Rather than just focus on government views of Japanese Americans or Buddhists, I tried to tell this history from the “inside out”. By narrating this history through specific and relatable individuals, the aspiration was to draw in an average reader into the lived experience of Buddhism and the wartime incarceration.

THAS: Your title, American Sutra, combines two words that seem worlds apart. The first is the name of a Western nation; the second, an Eastern word vaguely mysterious to English-speakers. Publishers tend to like the simple and familiar, so I wonder if that name presented a challenge in your road to publication or served as a hook.

Duncan Ryūken Williams: Yes, the title was a point of contention with the publisher (Harvard University Press) for a while, but ultimately they became convinced that by combining a Buddhist term with “American”, we can get at the dynamic tension at the heart of the book – is it possible to be both Buddhist and American at the same time? I had to point out that other similar terms – karma, nirvana, yoga – at an earlier point in American history was also deemed strange and mysterious, but that it’s through publishing works with such terms in their titles, that we effect familiarity. Plus, I think it’s a catchy title that’s easy to hashtag.

THAS: You write, “During his confinement, Rev. [Daishō] Tana often reflected on the fundamental teaching of the Buddha (sometimes called ‘the First Noble Truth’) that, no matter one’s status in society, life necessarily involves suffering.” Rev. Tana felt “incarceration provided an excellent opportunity for religious leaders to deeply experience isolation and humiliation.”

This made me wonder about the young people in camps like Tule Lake. It’s natural for any children to question and rebel against the norms of their elders even in good times. So how did leaders go about squaring this “opportunity” they saw with the grim fact that young people were spending some of the best years of their life locked behind barbed wire?

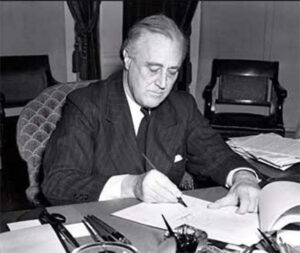

Duncan Ryūken Williams: Yes, many young people (who we should recall were U.S. citizens) struggled with the fact that their own country had put its citizens behind barbed wire without due process and did not permit the free exercise of religious despite President Roosevelt’s vision of fighting against the Axis on the basis of the “Four Freedoms”, including religious freedom. Buddhism served as a resource for both those who resisted the incarceration as well as those who accepted their situation. Buddhism provided a framework for those who served as well as resisted serving in the U.S. armed forces (33,000 served in both Europe and the Pacific) given the irony of serving whilst siblings and parents were imprisoned due to their race and religion.

THAS: Regular listeners know I’ll put a book about FDR’s infamous Executive Order 9066 at the top of my reading pile any day. But American Sutra is about more than part of the wider war. It’s about testing the First Amendment’s guarantee of religious freedom — and just like the free speech clause, it’s only really needed for what people would seek to repress. I imagine readers may say, “Oh, yeah, yeah. I know that story. Terrible. Roosevelt sent them the camps just because they were of Japanese ancestry.” How do you get those readers to stop and understand there’s more to the story, that faith also set them apart?

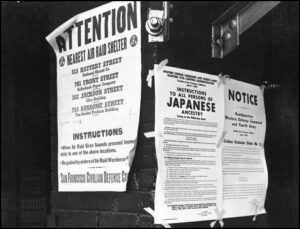

Duncan Ryūken Williams: The WWII Japanese American incarceration is usually understood as a terrible breach of the constitutional guarantees of due process and equality treatment under the law; that racism is what accounts for the targeting of this community when there was no mass incarceration of the German American or Italian American community despite the war against Nazi Germany and fascist Italy. But what I explore in the book is how the fact that over two-thirds of the Japanese American community was Buddhism played a major role in both how the initial internment and the mass incarceration after Executive Order 9066 unfolded. Indeed, Lt. Gen. John DeWitt explicitly notes – in his 1943 Final Report – how race, culture, and religion all played a role in his decision to undertaken the mass incarceration of anyone of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast. But American Sutra is also a story of how the community drew on their Buddhist faith to help them navigate a moment of dislocation, loss, and uncertainty; how Buddhist teachings, practices, and institutions played a decisive part in how the community endured this most challenging of times.

THAS: When I interviewed Kermit Roosevelt III (Theodore’s great-great-grandson and Franklin’s fifth cousin four times removed) about his novel, Allegiance, I mentioned being struck by the insidious language of Executive Order 9066. Nowhere did FDR specify Japanese or even Axis ancestry. Instead, he gives vague and unlimited power to military authority to do whatever they deem necessary. (It’s not unlike the broad powers a terrified Congress gave the presidency in the days after 9/11, fortunately without such consequences at home.) How do you hope readers of American Sutra will view President Roosevelt’s actions, especially as the generation that grew up idolizing him passes away?

THAS: When I interviewed Kermit Roosevelt III (Theodore’s great-great-grandson and Franklin’s fifth cousin four times removed) about his novel, Allegiance, I mentioned being struck by the insidious language of Executive Order 9066. Nowhere did FDR specify Japanese or even Axis ancestry. Instead, he gives vague and unlimited power to military authority to do whatever they deem necessary. (It’s not unlike the broad powers a terrified Congress gave the presidency in the days after 9/11, fortunately without such consequences at home.) How do you hope readers of American Sutra will view President Roosevelt’s actions, especially as the generation that grew up idolizing him passes away?

Duncan Ryūken Williams: Yes, you’re quite right about the language of the Executive Order being written up to be neutral so as to not reveal the racial and religious animus behind the order (confirmed by classified memos between Roosevelt and then Attorney General Francis Biddle and many intelligence memos shared between military intelligence and the FBI). There was certainly a lack of political courage on the part of President Roosevelt to stand up for American constitutional values at a time when it was most critical to do so. To her credit, we now know that Eleanor Roosevelt attempted to stand up for Japanese Americans in many ways behind the scenes.

THAS: One of the camp survivors, Star Trek actor George Takei, cut a very fine trailer for American Sutra. I attended an early screening of his play, also titled Allegiance, some years ago, so I was curious how you came to earn his backing for your project.

Duncan Ryūken Williams: I first met George Takei at a camp pilgrimage to Rohwer, Arkansas (one of the 10 War Relocation Authority camps) in 2004. Takei had spent his childhood in that camp as well as Tule Lake. He has been a tireless advocate for educating the public about this part of American history and for civil liberties more broadly. He grew up in a Buddhist family, was active in the YBA (Young Buddhist Association) movement, and in more recent years, married his now-husband Brad Takei in a Buddhist wedding. I asked George to provide a blurb for the book and record a video endorsement of American Sutra because of his involvement in both the Buddhist and Japanese American communities. I’m honored that he has been so supportive.

THAS: Thomas Jefferson named the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom one of the three achievements he wanted on his tombstone. (He left off being president, which gives us an idea how proud he was of the statute.) People love to quote and criticize Jefferson in equal measure, so I wonder if he had anything to say about Buddhism that might have been used at the time to urge wartime America to live up to the ideals in the Declaration of Independence, namely the “liberty” and “pursuit of happiness” being denied to those in internment camps.

Duncan Ryūken Williams: Jefferson’s ideals of freedom – whether religious or otherwise – are the bedrock to what constitutes being American. Yet, those ideals remain only aspirational if people don’t embody them. What I tried to show in American Sutra is that the Japanese American Buddhist community decided to embody and actualize the American promise of religious freedom, despite being told that they don’t belong and were even considered a national security threat.

Duncan Ryūken Williams: Jefferson’s ideals of freedom – whether religious or otherwise – are the bedrock to what constitutes being American. Yet, those ideals remain only aspirational if people don’t embody them. What I tried to show in American Sutra is that the Japanese American Buddhist community decided to embody and actualize the American promise of religious freedom, despite being told that they don’t belong and were even considered a national security threat.

THAS: Readers may know that Jefferson originally put “pursuit of property” in the Declaration’s first draft. Even after VJ Day when the camp doors flew open, internees couldn’t just pick up their lives where they left off. They’d lost everything, and weren’t compensated until 1988, when President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act.

HE stated at the signing ceremony, “The legislation that I am about to sign provides for a restitution payment to each of the 60,000 surviving Japanese Americans of the 120,000 who were relocated or detained. Yet, no payment can make up for those lost years. So, what is most important in this bill has less to do with property than with honor. For here, we admit a wrong; here, we reaffirm our commitment as a nation to equal justice under the law.”

If it was me, I would be tempted to say keep your money and give me back those years of my life. Yet resentment such as that can be a prison of its own. How did those 60,000 survivors view the apology and compensation through the lens of Buddhism, because it’s hard to say you’re sorry and just as hard to forgive.

Duncan Ryūken Williams: The presidential apology did mean a great deal to the community, especially for members of the community who felt so conflicted (and even shameful) about the difficult experience during the war. To have the President express an apology and provide symbolic financial compensation meant something. To right a wrong is difficult and to then calibrate feelings of loss, rejection, and resentment has been an inter-generational one, with some drawing on their religious faith as during the war, to attend to this experience in a way that lingering bitterness could be released or at least reframed.

THAS: In the prologue of American Sutra, you write that we tend to view U.S. history east-to-west, “But what happens when we flip the map?” It occurred to me that we read English left to right, and yet that’s not how we view the expansion of the U.S. map. How did Americans of Japanese descent who were third- or fourth-generation citizens view their ancestors’ history differently from those who arrived on the the East Coast, say, through Ellis Island?

Duncan Ryūken Williams: Usually we assume that the American story is one of westward expansion, with pioneers trailblazing ever further west on the continent, even across the ocean to Hawaii and the Asia Pacific. At times, this westward expansion of the United States has even been seen as ordained by God; as the fulfillment of a manifest destiny of the nation. But for the Asian American community, which has been a part of the building of this nation for over 150 years, their journey, settlement, and conception of America is an eastward journey. When we flip the map, we see for the first time that America is a nation of not just one migration narrative across the Atlantic, but many different migrations from various corners of the world.

THAS: You discuss chaplains in the U.S. Army, none of them Buddhists – and you were a chaplain at Harvard yourself. One of the soldiers who deploys and doesn’t have the benefit of clergy, is Staff Sgt. Kazuo Masuda, whose acts of bravery earn the Distinguished Service Cross where he holds off the Germans for twelve hours, using his helmet not for protection, but as a base to fire mortars. He later sacrifices his life to save his men. (If he were a character in a novel, an editor would reject Sgt. Masuda’s heroics as too fantastic to be believed.)

THAS: You discuss chaplains in the U.S. Army, none of them Buddhists – and you were a chaplain at Harvard yourself. One of the soldiers who deploys and doesn’t have the benefit of clergy, is Staff Sgt. Kazuo Masuda, whose acts of bravery earn the Distinguished Service Cross where he holds off the Germans for twelve hours, using his helmet not for protection, but as a base to fire mortars. He later sacrifices his life to save his men. (If he were a character in a novel, an editor would reject Sgt. Masuda’s heroics as too fantastic to be believed.)

In American Sutra, you draw on untranslated diaries, letters, and new oral histories to flesh out the stories of men like Masuda. How did you go about approaching descendants, and did you find them eager to share what their ancestors had done to help win the war for a nation that didn’t fully trust or understand them no matter how much blood they spilled in its defense?

Duncan Ryūken Williams: I had the opportunity to speak to a number of WWII veterans for the book, in their campaigns both in the Pacific (the Japanese American who served in the Military Intelligence Service [MIS] as translators, prisoner interrogators, and code breakers shortened the war by two years and saved over a million American lives according to the U.S. Army) and European theaters (were the serrated Japanese American unit, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, was on the front lines of the campaigns in Italy, France, and Germany and recognized as the most decorated unit of its size and length of service of any unit in U.S. Army history). I had to rely on these oral histories combined with army documents, diaries and correspondence from the war, and the excellent scholarship of other researchers. Again, the fact that the vast majority of those who served were Buddhist – but yet denied chaplains and dog tags that acknowledged their religious affiliation until after the war – is a lesser known aspect of their service to their country.

THAS: I read a story recently about the “Greek Freak,” Athens-born Giannis Antetokounmpo. He’s of Nigerian ancestry and converted to the Greek Orthodox Church. In the story, they polled people in Greece if you had to be a member of the church to be Greek, and the response was in the high 90s that you did — and, unlike the U.S., European nations do not have birthright citizenship.

American Sutra looks at the prevailing feeling in the World War 2 U.S. that to be fully a citizen, you had to be a White Anglo-Saxon Protestant – not Catholic, Jewish, Eastern Orthodox, Buddhist, etc. But let’s “flip the map” again to ask how the internees in those camps viewed those outside. I guess today, we’d ask if they did any outreach, or did they not see the danger of ignorance until they heard a knock on the door?

Duncan Ryūken Williams: I write in American Sutra about the small number of allies of the Japanese American community – of many different racial and ethnic backgrounds – who risked being called a “Jap lover” or worse by the majority of the public. The ties of friendship in some neighborhoods, fellowship between co-religionists, and the advocacy of those who believed in upholding constitutional civil liberties even in the midst of war all gave hope to the incarcerated Japanese American community. These allies protested the incarceration, stored belongings and made trips to the camps to transport household items, and helped the community with jobs and housing during the post-war resettlement. So, these friendships across ethnic boundaries did effect some difference, but the vast majority of the public simply viewed the forced removal and incarceration as a wartime necessity.

THAS: You write in American Sutra you write that the Japanese American Buddhists who “ended up” (we can hardly say “settled” or “moved to”) Midwestern and East Coast cities, “served as a vanguard in building new Buddhist sanghas across the United States.” What is the legacy of those enclaves, especially when veterans of the Nisei (American-born soldiers of Japanese immigrant parents) regiments begin to return home?

Duncan Ryūken Williams: Building Buddhist communities in area far removed from their homes on the West Coast was certainly a challenge, but the legacy of spreading Buddhism to all parts of the U.S. is postwar interest in the religion by non-Asians. Today, Buddhism is much more a part of the American religious and cultural landscape that could have ever been imagined back in the 1940s. In terms of Nisei veterans, especially in places like Hawaii, they played a major part in securing the community’s engagement in all aspects of American mainstream life, including politics. We could say that the legacy of their service is what has led to the successful careers of Buddhists like the current governor David Ige and the current senior U.S. Senator Mazie Hirono.

THAS: I interviewed 103-year-old Lt. Jim Downing about this book The Other Side of Infamy. He was then the second oldest survivor of the Pearl Harbor attack. He had no ill feelings for people of Japanese descent, but he did struggle when he had to meet Japan’s Pearl Harbor attack commander, Mitsuo Fuchida. Here was the man who’d orchestrated killing his friends, and sinking his home, as he put it, the USS West Virginia.

Fuchida showed genuine remorse and shame, and the two old soldiers found common ground over both being devout Christians, a missionary having given Fuchida a Bible. Lt. Downing said, “I could embrace and forgive him as a brother.” What does that story say to you in light of American Sutra and finding?

Duncan Ryūken Williams: In this particular case, I think it shows how co-religionists might be able to overcome national boundaries, even the barriers that would naturally emerge from war and the bitterness that would come from the loss that inevitably accompanies all wars. In American Sutra, I recount the story of Richard Sakakida; one of only two Japanese Americans captured by the Japanese Imperial Army during the war. He undergoes excruciating torture in the hands of the notorious Kempeitai military police, but ultimately forgives his torturers after the war when he hunts the three individuals who tortured him in his role as the head of the war crime tribunal in the Philippines. He drew on his Buddhist faith to forgive them and postwar even stayed in touch with one of his former torturers. Sometimes the deeper the faith life, the easier it is to find a way to find peace and reconciliation.

THAS: I like to ask authors to make their pitch when I wrap up interviews, so have at it. Why should readers pick up American Sutra to learn about this challenge to religious freedom and national identity on the U.S. home front of World War 2?

Duncan Ryūken Williams: There are a lot of good books out there on the WWII Japanese American incarceration, but this is the first that takes religion (Buddhism) into account, both for why internment happened as well as for how it served as a spiritual refuge to help people survive and persist despite the dislocation and loss. This history is not just about Buddhism and WWII – under martial law in Hawaii, behind barbed wire in the camps, or in the U.S. military – but about the enduring question of what it means to be American. Please check out the book if you have an interest in ongoing discussion of how race, religion, and American belonging come together or how American ideals like religious freedom is viewed by those who came to America from Asia.

THAS: Duncan Ryūken Williams, thank you so much for taking the time to discuss American Sutra: A Story of Faith and Freedom in the Second World War, giving us fresh voices in the examination of the internee experience on the U.S. home front in World War Two. May we never forget.

Duncan Ryūken Williams: Thanks so much Dean!